On November 9, 1979, just ten years before the fall of the Berlin Wall, United States National Security Advisor Zbigniew Brzezinski was awakened at three in the morning by his military assistant, General William Odom. The warning system had detected at least 200 Soviet missiles flying towards North American territory. A few moments later, there were already 2,200. There were only a few minutes left to notify President Jimmy Carter and order a response. A little later the error was detected: a wrong magnetic training strip had been inserted into the North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD) computer, simulating a Soviet attack.

Dubbed the “magnetic stripe incident” or “the 3 a.m. call,” documented years later in declassified files, this alarming situation was not the only near-failure that could have triggered a nuclear catastrophe during the Cold War. In several instances, the Soviets were misled into believing they were under attack. However, in the face of these unfounded alarms and actual crises, prudence consistently prevailed when humanity stood at the edge of destruction.

Psychological Undercurrents of Nuclear Deterrence: Playing with Honor and Fear

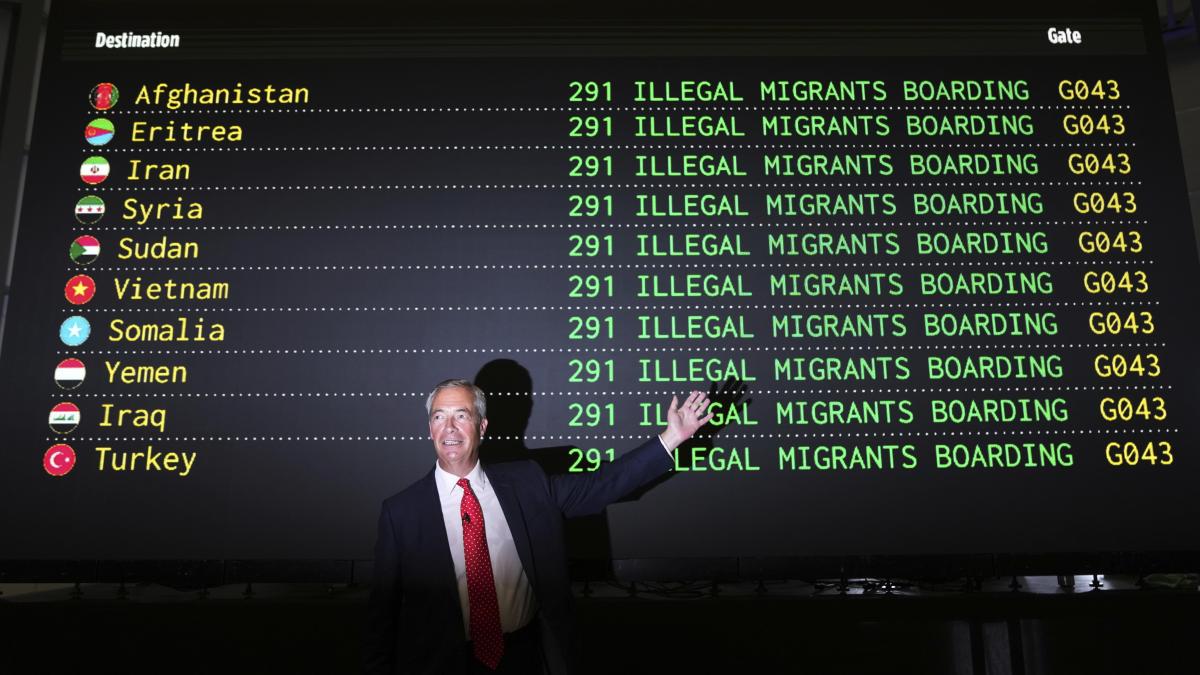

Vladimir Putin’s posturing periodically stirs fears of an atomic catastrophe. His announcement of altered doctrine yesterday is just one more step in the policy inaugurated after the annexation of Crimea in 2014. Then, he proclaimed that the peninsula was Russian territory, and thus could warrant protection even through nuclear means. Since the invasion in February 2022, these grim warnings have proliferated.

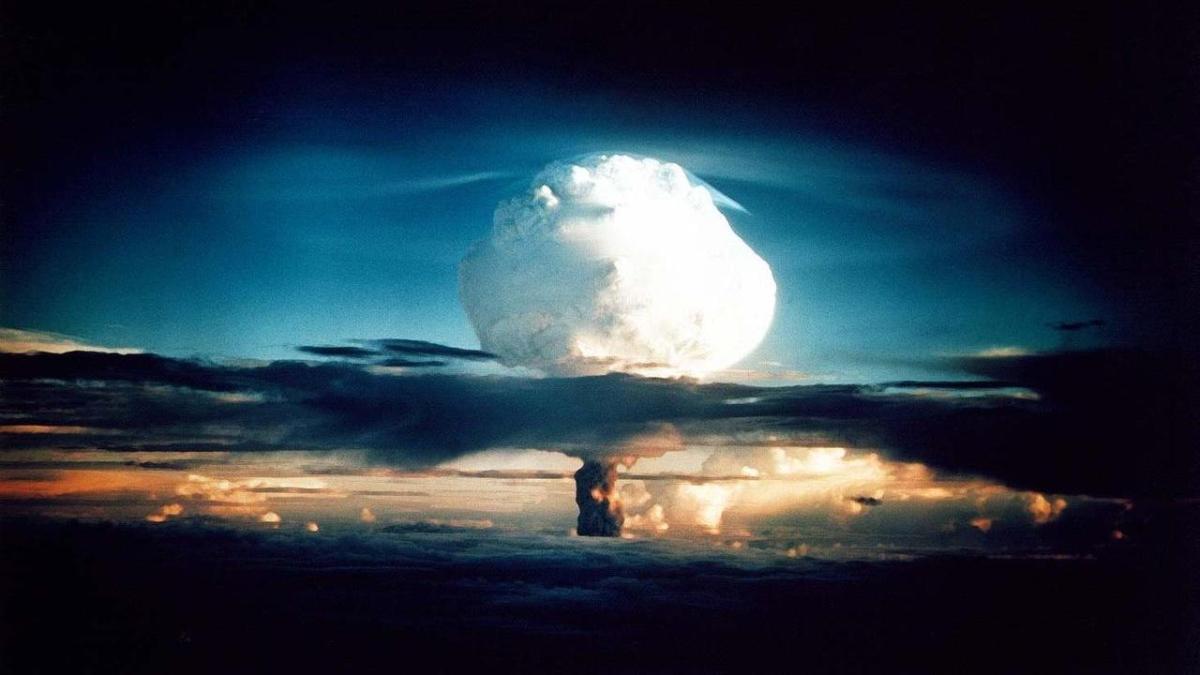

In his latest work, Pax atomica? Theory, practice and limits of deterrence, Bruno Tertrais emphasizes that the catastrophes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August 1945 could have been repeated numerous times had it not been for good judgment among belligerents and, crucially, sheer luck.

Among the most notable dangers was the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, a 13-day confrontation that remains a defining moment of the Cold War. Reflecting upon that episode, an elderly Robert McNamara, Secretary of Defense during John F. Kennedy‘s administration, candidly confessed that the world stood on the brink of atomic war. He recounted how Fidel Castro later divulged that he would have endorsed a nuclear response against the United States in the event of invasion, even at the cost of Cuba’s total destruction.

Cuba was the flashpoint for the gravest risk of nuclear conflict between the superpowers. Yet just a decade prior, the U.S. had seriously contemplated deploying nuclear bombs to conclude the Korean War (1950-1953), as advocated by General Douglas MacArthur. The Pentagon readied B-29 bombers at bases in Guam and Okinawa as the situation escalated. Ultimately, Presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower refrained from taking that drastic step, deciding that containing North Korean communists at the 38th parallel was sufficient in what became a frozen war that still persists today.

In his text, Tertrais documents numerous scenarios where deploying nuclear weapons was either considered or threatened, including significant crises involving

Maoist China in the Formosa Strait during the 1950s, Moscow’s actions during the Suez Crisis in 1956, U.S. threats during the Vietnam War, and Israel’s stance in relation to Egypt during the 1973 Yom Kippur War.

Nuclear deterrence hinges heavily on psychological factors. Its success relies not solely on possessing atomic weapons, but rather on convincing the potential adversary of a willingness to deploy them. This concept of “strategic ambiguity” plays a pivotal role. It is a hallmark of the French nuclear arsenal; the French President alone designates the vital interests necessitating a nuclear response, leaving allies uncertain of the precise circumstances under which they might invoke nuclear action.

Among the most disturbing elements of Putin’s recent decree is that Russia’s critical interests appear explicitly defined, allowing little room for ambiguity regarding the threshold at which the apocalypse draws near.